Menu

- Introduction

- Types of Domestic Violence

- Habitual DV Offenders

- Power and Control

- The Cycle of Violence

- Counter-Intuitive Victim Behaviors

- Mandatory Arrest

- Lethality Factors

- Protection Orders and Bond

- Firearm Relinquishment and Affidavits

- Recantation

- Consulting the Victim about a Plea Offer

- “No Face, No Case”

- Prima-Facie Case Requirement

- Preparing for Trial

- Trial

- Sentencing

- Victim Resources

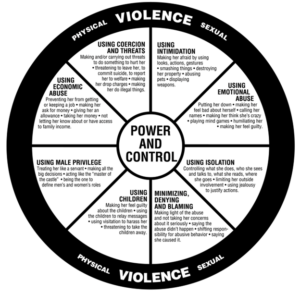

There are many ways abusers exercise power and control over their victims, from more subtle methods like asking about the victim’s whereabouts to more brazen methods like making a victim show the abuser her phone to prove she wasn’t “cheating” on him.

The flow of power and control in domestic violence is almost always one-directional, meaning the power and control flows—through coercion, isolation, manipulation and other methods—away from the victim toward the abuser. Although you may hear defense attorneys and others claim “it was just a toxic relationship,” or “there was a lot of blame to go around,” such claims rely on a misunderstanding of the monopoly the abuser has over power and control in the relationship. Such claims attempt to falsely equate victim conduct, which is usually defensive and reactionary in nature, with offender conduct, which is usually controlling and coercive.

The “Power and Control Wheel” is a well-known way to describe the methods an abuser might exercise power and control over the victim in a DV relationship.

In a DV case, as you prepare for trial, look for and emphasize evidence of power and control. In most DV trials, this kind of evidence will help prove your case and establish it is a case of domestic violence. If the victim is cooperative, consider requesting a DV detective or a skilled investigator interview the victim to identify examples of the abuser’s exercise of power and control. The introduction of such evidence is especially persuasive when paired with a generalized (“blind”) expert on domestic violence who can explain to a jury how such dynamics characterize DV relationships and explain confusing victim conduct.

Resources

Recorded Trainings

Prosecutor’s Guide to Utilizing Trauma Experts in Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence Cases